Inspired by the years of reconstruction, this blanket tells a story of resilience, comfort, and new beginnings. In a time when much had been lost and people searched for stability in the familiar, a blanket offered warmth, security, and a sense of home.

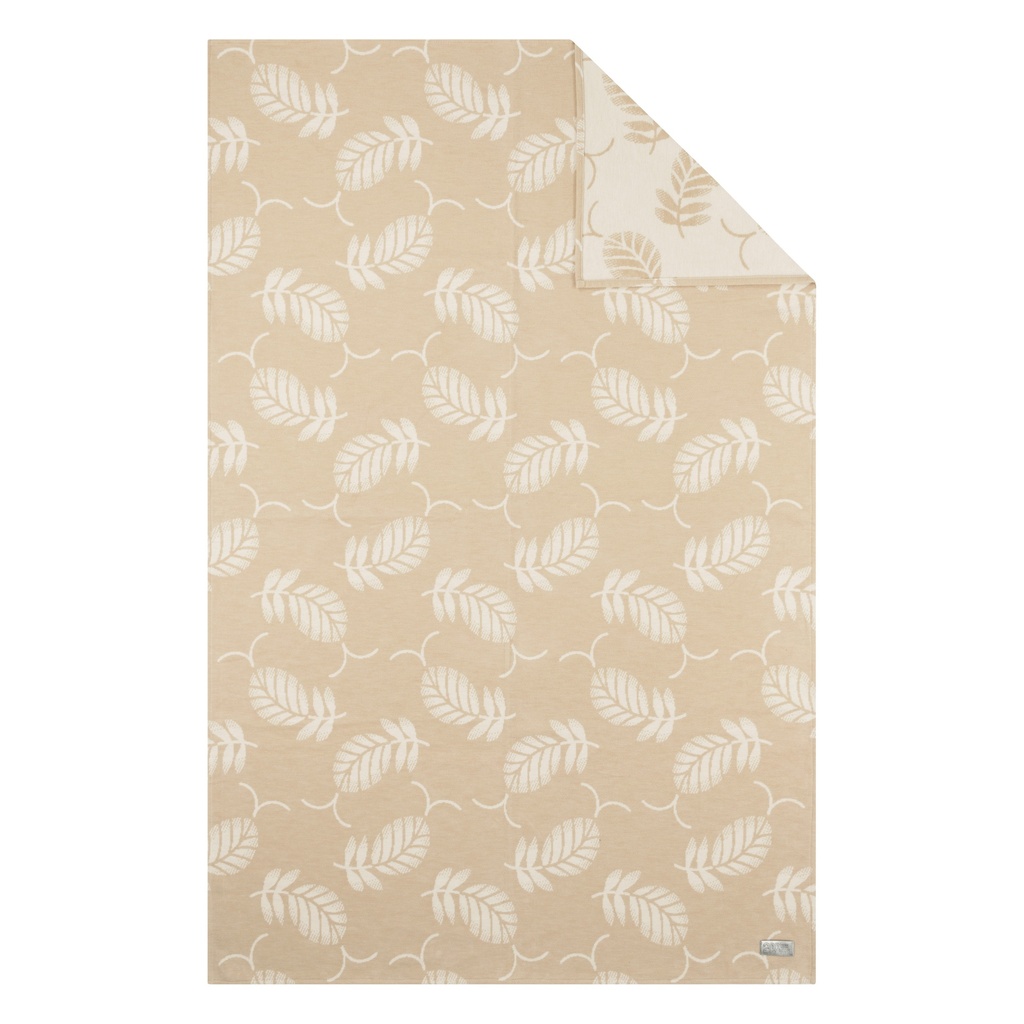

With its timeless design and soft, inviting character, this blanket reflects that spirit of renewal with its subtle leaf motif in apricot and natural white. Crafted from a premium cotton blend, it is wonderfully plush and gentle against the skin, providing comforting warmth on chilly evenings and a reassuring sense of coziness in any space.

Generously sized and made for everyday living, it is both practical and luxurious: machine washable and dryer friendly, with a velvety surface that remains soft and beautiful wash after wash.

A tribute to enduring craftsmanship and the strength of starting anew—this blanket is a symbol of comfort, hope, and home.

Made of 100% GOTS certified organic cotton and certified by OEKO-TEX® Standard 100 which ensures that the blanket contains no chemicals harmful to humans or animals.

Amid smoking ruins, Germany began to breathe again. Millions of cubic meters of rubble lay everywhere; entire cities had been destroyed. In many places, every second apartment was considered uninhabitable. Housing was scarce, and displaced people in particular were left quite literally out on the streets. In interior design, people remained rooted in tradition, searching for stability in what was familiar. There was little one could afford.

Four Generations – Facing a New Task

One hundred and twenty years had passed since Josef Philipp Beckmann founded his textile trading business. Four generations had carried the company through highs and lows. Yet nothing could have prepared them for what came after 1945: destroyed factories, lost markets, an uncertain future. How do you rebuild something from nothing? The Beckmann family faced this question as well.

The Art of Survival

In everyday life, ingenuity became a means of survival. Objects of war were turned into household necessities: steel helmets served as bowls, gas mask containers as buckets. Clothing was patched, mended, and altered. Uniforms became civilian garments, parachute silk became underwear, and blankets were turned into coats. Every thread mattered.

At the same time, hunger prevailed. Food ration cards often amounted to only about 1,500 calories per day on paper—yet in reality, allocations were frequently even lower. The winter of 1946/47 entered memory as the “hunger winter.”

Between Despair and Hope

Despite deprivation and hardship, the mood was not defined solely by despair. Witnesses spoke of the “joy of mere survival.” After six years of war and countless losses, simply being alive felt like a gift. This mindset transformed resignation into determination.

The Rubble Women and a New Beginning

A symbol of this era were the Trümmerfrauen—the rubble women. With bare hands and simple tools, they cleared stone after stone. For many, it was exhausting labor for little pay, yet also a visible sign that a future was once again possible. Every cleared street meant a piece of new life.

A Thread Taken Up Again

Reconstruction began for the Beckmanns sooner than one might have thought possible. The much-invoked sense of community within the company proved to be real: only days after destruction, employees began clearing debris and repairing what they could. Using fragments from the ruins, they restored twelve weaving machines.

In November 1945, J. Beckmann Nachfolger resumed work with a small weaving operation of exactly these twelve looms—modest in scale, yet immense in symbolic power.

By 1946 there were 36 machines, by 1948 around 159, and by 1949 finally 237. The company produced blankets for refugee camps and fabrics for the mining industry—practical goods urgently needed in those years.

At H. Beckmann Söhne, operations resumed in July 1947. Since senior director Ludwig Beckmann was already well into his eighties, and his eldest son Heinrich did not wish to take over leadership after returning from the war, the company relied on outside expertise. On May 1, 1947, Max Wagner became the first external managing director. Thanks to his efforts, production could restart just two months later.

A Heavy Legacy

The post-1945 period also brought confrontation with the past. During the war, companies such as H. Beckmann Söhne had produced using forced labor, and J. Beckmann Nachfolger had been awarded the title of a “National Socialist model enterprise” in 1942. Toward the end of the decade, the heirs of the expropriated Jewish weaving mill Cosman, Cohen & Co. came forward with restitution claims, which were quickly resolved.

Reconstruction was not only a material process, but also a moral one.

The Boom Begins

By the end of 1946, Germany was still a land of ruins. Yet those who looked closely could already recognize the first signs of the coming economic boom. People were working again in workshops, offices, and factories. The Beckmann companies, too, stood on the threshold of a new chapter.

To install this Web App in your iPhone/iPad press

![]() and then Add to Home Screen.

and then Add to Home Screen.